Tidbits

THE ACADEMIC MOTTODuring the 1600s, certain obligations were imposed on the many Academies that were coming into being, including having a specific name, having their own motto and choosing a patron saint. Thus, in the history of the Teatro Grande, the Accademia degli Erranti decided to avail itself of the divine protection of St. Catherine of Siena and adopt as its own the image of the crescent moon surmounted by the motto Non Errat Errando. This “slogan” took on a greater and more complete meaning when it was taken up in the entrance over door of the Accademia’s headquarters.

“Hic reparatis Hephesi ruinis / Cynthia comitata musis vallata Amazonibus / non errat errando. /

Haec si cupis intueri quis quis es / uno dempto Herostrato / ascende viator.”

The text is written in an intentional emphatic Latin and, through reference to the Greek myth of Cynthia (in Latin Diana, Goddess identified with the Moon), gives us back the basic principles of the Accademia. Some argue that the reference to the myth of Diana comes from the fact that in the area of the convent of St. Faustinus, the first site of the Accademia, there was in Roman times a temple dedicated to the goddess Diana. Hence, just as Cynthia escaped from the burned ruins of the temple at Ephesus and, accompanied by the Amazons, found a refuge where she could begin her activity anew, the Academicians also wandered away from their first residence, to establish the Accademia’s permanent seat in this new place. This wandering, which can also be interpreted broadly in the loose sense of “to wander, to err,” is not to be considered wrong in that it is a way to begin again and still serves to strengthen the store of experience and to continue activities in the best possible way. Thus, anyone who is interested in learning more, except those who deny the importance of the arts and intelligence, as Erostratus had done by setting fire to the temple of Diana, is invited to “ascend,” indicating by this expression both the literal meaning of the verb (to ascend the stairs of the academic seat) and the metaphorical meaning that indicates the possibility for those who attend the Accademia to increase their knowledge, to advance culturally and to rise to the knowledge of the arts.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Ridotto and the rooms adjoining it were often used as a place of entertainment and recreation: games of chance were held there, often reserved personally for the senior French officers of the Grande Armée, then present in Brescia following the Italian Campaign. It is curious to consult the Regolamento Per l’Esercizio de’ Giuochi d’Azzardo nel Ridotto di Brescia (Regulations for the Exercise of Games of Chance in the Foyer of Brescia) specially drafted in 1810 to establish the behavioral norms to be observed during game nights in the Foyer. The Regulations are preserved today in the archives of the Grande.

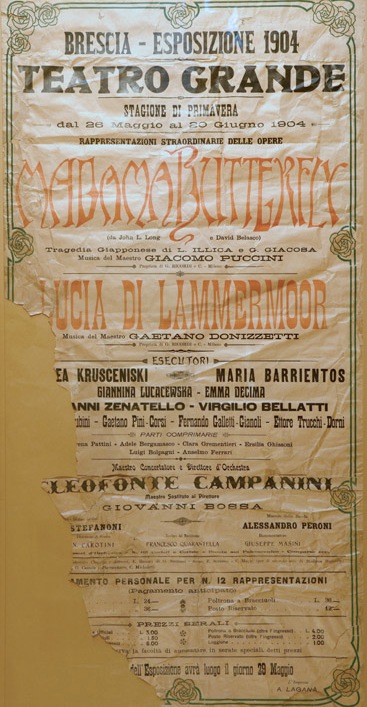

Giacomo Puccini chose the subject of his sixth opera after attending David Belasco’s one-act tragedy of the same name in London in July 1900, which appeared in 1898. On the evening of Feb. 17, 1904, despite the anticipation and great confidence of its creators, Madama Butterfly fell resoundingly at the Teatro alla Scala in Milan.

The fiasco prompted the author and publisher to immediately withdraw the score and subject the opera to a thorough revision that made it more agile and proportionate. In the new version, Madama Butterfly was enthusiastically received at the Teatro Grande in Brescia just three months later, on May 28, 1904, a performance also attended by King Vittorio Emanuele III. Interpreter personally chosen by Puccini for the role of Butterfly for the occasion was Solomiya Krushelnytska, one of the most successful Ukrainian opera singers of the 20th century. From that day Madama Butterfly began her second, successful existence.

Recite the Brescian chronicles of the time: “…Puccini had yesterday triumphantly won. Seven encores, twenty-five calls…the Theater was extraordinarily packed…the boxes were crowded…an enchanting sparkle of beauties, of diamonds, of lace…few times has there been such an immediate success…justified by the intrinsic value of the opera in its principal part;…but also by its performance, which could not have been better….”

And so Puccini thanked in a letter to the Deputation, “Already twice Brescia, the cultured and gentle, has made me welcomes that will be indelible for me. With a moved heart I would also like to let the public know my feelings and to thank wholeheartedly my friend Mascheroni, the valiant and zealous performers of Manon, and finally all those who kindly wanted to give me a very dear and precious memory for me. But I do not feel myself capable of so much, and therefore by addressing myself to this honorable Deputation of the Teatro Grande I am sure to find in it an eloquent interpreter of my most vivid gratitude, which I also tribute to it.”

As for the theater environment, it is known for certain that there were strict ushers in charge of controlling the entrance so that only noble, or otherwise authorized persons were allowed access, strictly entered wearing the “bautta.” The bautta was a silk or velvet mask that covered the upper part of the face, leaving the mouth free. Only when one was inside was it possible to uncover one’s face, entirely or even partially. Today’s ushers – “maschere” in Italian, meaning “masks” – presumably retain their name as a result of the aforementioned duties.